In retrospect, the Prince album that is most often compared to Beck's 1999 opus is not Dirty Mind but Around the World in a Day - as an example of artistic hubris following a commercial breakthrough. No matter. I still think Midnight Vultures is underrated (though I'd tip my hat to Guero as Mr. Hansen's second greatest work). What Beck's career has shown is that he's not so much interested in "topping himself" as exploring as many facets of himself as he can, a la Bowie. Oh, and, your videos are a mouse click away.

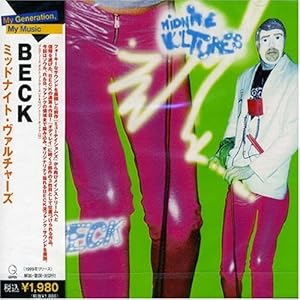

So you wouldn't have thought that Beck Hansen could top himself. I didn't. Apparently he didn't either. And definitely the two leading journals of rock criticism, Rolling Stone and Spin, dismissed the possibility when they went to print with their respective "best of the 90s" issues several months before Beck slipped in his latest, Midnight Vultures, just ahead of the millennial (sic) deadline. And if, ultimately, he couldn't top the sublime Odelay, he sure had a lot of fun trying - and it shows.

The funny thing is, he didn't even think Odelay was all that great. "At the time," he admits, "I thought the album was kind of behind." (Similarly, when Radiohead emerged from the studio with their masterpiece OK Computer, they had no idea who could possibly appreciate it.) But Odelay turned out to be ahead - way ahead. To be sure, he benefitted from low expectations in a way that he can't anymore. After his improbable MTV hit "Loser" blended folk with hip-hop and an indelible slide riff, he could easily have been dismissed as a one-hit wonder. And indeed, his haphazard stage shows of the time wouldn't have disabused anyone of the notion. While Beck had been performing since he was a small child, he was the first to admit that he had no idea how to "mach schau," as the clubowners on the Reeperbahn advised the young Beatles. So mostly he just hung out on stage and jammed with his buddies.

To take his music to the next level, Beck knew he had to come up with songs that could make for a compelling live show, which is how Odelay was originally conceived. But before the born-again Beck started wowing the crowds, he repaired to the studio and pulled together an unprecedented amalgam of American musics, from Delta blues to lo-fi-slacker rock, cutting-edge techo to mariachi horns, bluegrass jams to hip-hop beats, punctuated with witty samples from old movies and TV shows. It was the perfect album for its moment, instantly grabbing you by the spine; it spawned three hit singles and snagged the top spot in the Village Voice's prestigious Pazz'n'Jop critics' poll.

And it transformed young Beck into a compulsive showman in Nudie jackets, the skinny white kid doing James Brown kneedrops and revving up the crowd with his self-parodying antics. He toured behind it for over a year, sharpening his stage presence, and perhaps putting off the requisite followup album. So insistent was the buzz that followed him, both artist and record company insisted that the next album, Mutations, was "not the real follow-up" to Odelay. It was just some stuff that Beck had pulled together in the studio to fulfill contractual obligations. Unlike his pre-"Loser" tossoffs, though, Mutations had both a polished sheen and an amiable air of professionalism. The Brazilian-hommage single "Tropicalia" was a minor hit, and the disc itself came in at #11 in that year's Pazz'n'Jop. But since you can only get away with calling it an "interim effort" once, the pressure was now on.

Aside from a few guest appearances on stage and in other folks's studios, Beck made Midnight Vultures his full-time job for nearly 14 months. Using new computer technology, he meticulously micro-synchronized each sample to the underlying complex of beats. But unlike Odelay, which he pieced together in his home studio with producers the Dust Brothers, Midnight Vultures used a studio band to lay down tracks over which the many flavors of cake frosting were collaged.

From the beginning, the record was conceived of as something as sex-obsessed as Prince's Dirty Mind or Madonna's Erotica - except that Beck could never attempt something like that with a straight face. So the absurdity of our sex-obsessed culture at the turn of the century, with our surgically-enhanced physiques, overpriced mating feathers, solipsistic fetishism, and presidential blowjob scandals, oozes from every funky groove. And groove along it does, with R&B horns, computerized backbeats and Mr. Hansen's brand-new falsetto croon. Top himself? How could you doubt it?

Since I can't avoid overhyping this delightful wink at the end of the decade, let me just take the advice of my college professor, who said that if you praise somone, you should lay it on with a trowel. So then, in terms every Baby Boomer can understand: Beck is like the Beatles in his mastery of contemporary recording technology and his popularization of underground sounds. He's like the Stones in his great love of black music. And he's like (pre motorcycle-crash) Dylan in his whimsical embrace of surreal imagery and rhymes, and in the fact that he changed the world of rock forevermore. With Odelay, Beck became a genre unto himself, called collage rock for lack of a better pigeonhole. But without his innovations (built, to be sure, on the achievements of hip-hop and avant-garde musicians before him), a whole new set of genre-blending musicians, from Garbage to Sublime to Cibo Matto to Cornershop, would have been unthinkable.

But he's unlike those 60s icons in that he's far from the most popular artist of his times, an honor that probably belongs to Garth Brooks. Nowadays rock's market share is overshadowed by mainstream country and especially the mighty hip-hop juggernaut, now in its third decade. Recently John Hiatt predicted that the popularity of hip-hop would help bring kids back to rock music. And at the midnight sale where I purchased Midnight Vultures, the all-white college crowd was lining up not for Beck, but for the Beastie Boys (who combine hip-hop and rock with much more of an accent on the former), as well as the more traditional rock acts Dave Matthews and Phish. What's left of the rock audience is more fragmented than ever, with various subcultures following neometallic acts like Korn, grungy white rappers like Limp Bizkit and post-industrial angst from Nine Inch Nails.

But rock was born from the marriage of black and white folks' music, and the courtship has been rekindled over and over again. In that sense, Beck is like Elvis: a white kid who grew up immersed in a variety of cultures and instinctively blended them into something all his own. So like the man said, rock is dead; long live rock.

No comments:

Post a Comment